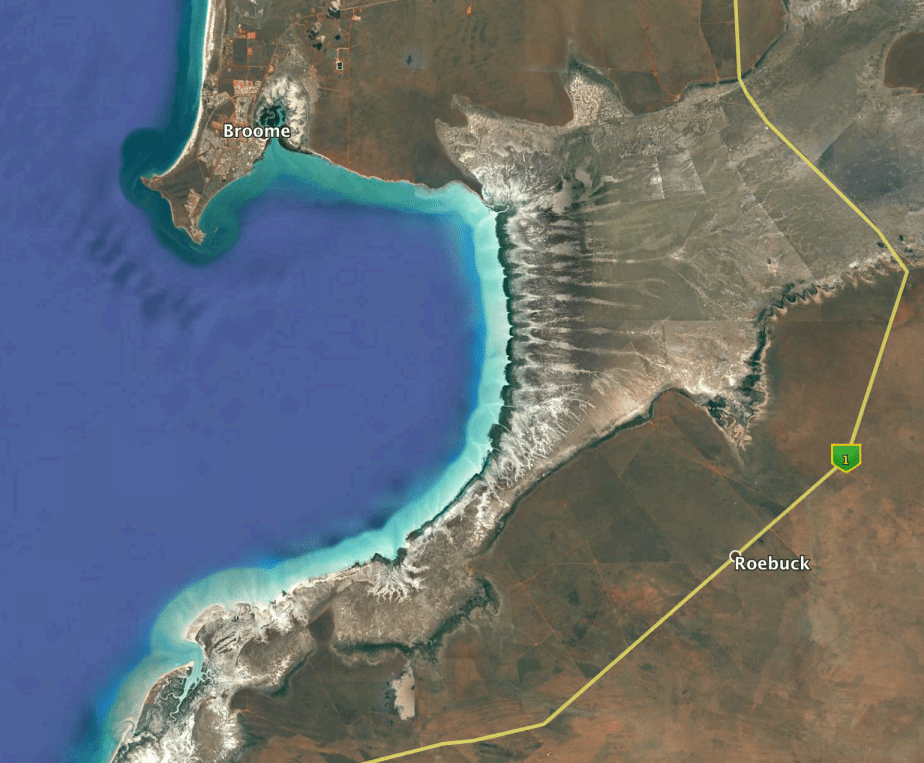

As I point out from time to time Roebuck Bay is the Shorebird Capital of Australia. The shores are in part accessible by car from Broome. Other parts are more of a challenge to reach and are therefore less well studied and less frequently disturbed. Bush Point is 22km due south of the Port of Broome and not easily accessible except by boat. That’s not to say that other means have never been employed. Over the years hovercraft and 4WD vehicles have been used but boat is the most practicable. However boat does have the drawback of limiting time ashore to about one hour on each side of high tide. It’s the 10 metre tides that expose the mud that feeds the birds that make the bay the Shorebird Capital of Australia. Deal with it.

The other day I had the enormous privilege to accompany a party of keen volunteers ably led by Chris Hassell of the Australian Wader Studies Group on the regular winter count at Bush Point. The project has been running for 24 years. Parks and Wildlife provided the boat, a landing craft style catamaran that ripped along effortlessly at 25 knots across the bay. The front was lowered and we stepped off into a few inches of water, not a crocodile in sight.

A winter count is revealing. A migratory shorebird with any intention of breeding is somewhere between here and Siberia. Birds on the beach are mostly too young to breed. The age that they reach maturity varies from species to species. Some species will return north in their first year others spend one or more years in the southern sunshine before going. As a rule the bigger birds wait longer than the smaller ones. If summer counts are available comparing the two gives some indication of breeding success over the recent past.

Our priorities were straight forward. First and foremost to count the migratory shorebirds, secondly the resident shorebirds and we were to avert our gaze from anything not a member of the Charadriformes. This is ornithology, guys, not merely bird watching. We were divided into two groups and sent forth to count. Easy …

Well, easier when they’re on the ground and keeping them on the ground means a little stealth and maintaining a considerable distance. Identification and counting is done with telescopes.

Opportunities for photography were very limited. If a group flew by you might just get a shot …

An hour after high tide the volunteers reconvened for the journey home.

So what did we find? Two parties covered about 4km of beach amassing a total of 13,400 individual migratory waders representing 20 species. Red-necked Stints were the most numerous and these would be in their first year of life. Whimbrel and Great Knot were well represented.

In the few minutes before being put on a short leash and obliged to trudge for miles through soft sand while being sun burnt and bitten by sand-flies (Gallipoli and Normandy were worse, I believe) I did get to point the camera at non-target or low priority species …