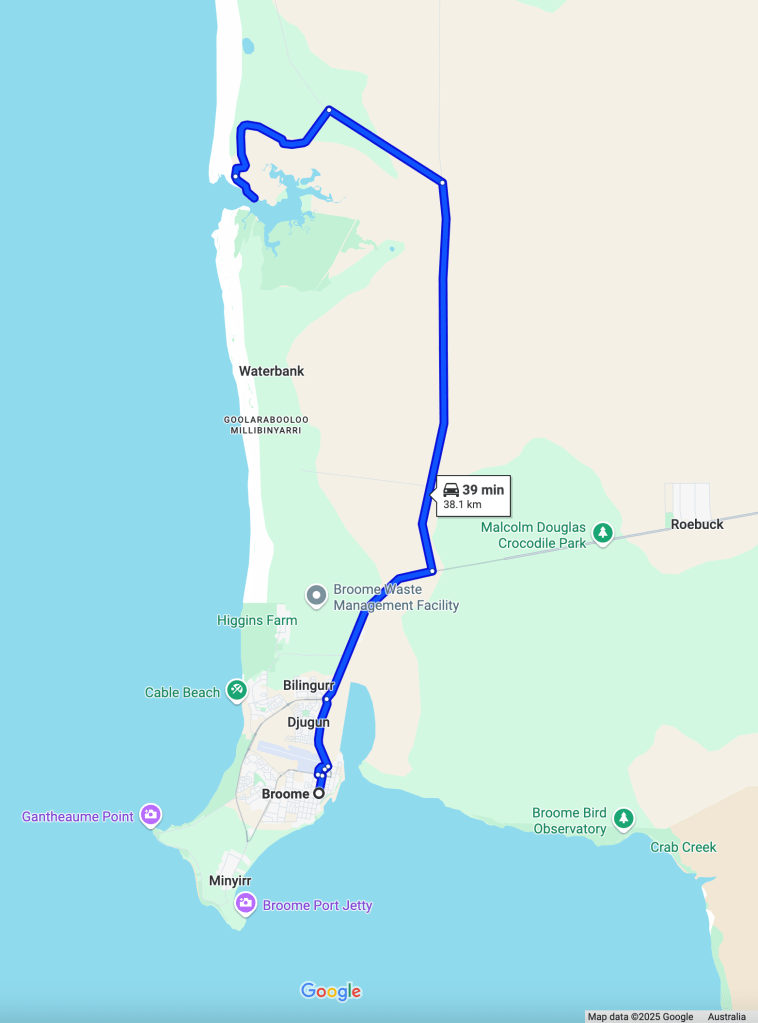

More specifically a little chat about the calendar game. Readers in for the long haul know all about the calendar game. For those not familiar with it, it starts on January 1st and you are in the game so long as you have seen more birds in the year than days have elapsed. If you fall behind the calendar you are out. So on January 1st at Taylors Scrape, ~70km from Broome, at 5.31 am I pressed the button “Start New List” on eBird mobile and the game commenced. By the end of the day I was safe well into February.

There is, in birding, a concept called the Big Year. It’s like a super calendar game where you chase all over a region of your own choice, twitch every rarity, get on every birding boat trip, visit every habitat, spend a fortune on travel, stay awake through every very long drive, sleep rough, eat poorly and pay no heed to your impending divorce.

The calendar game is more genteel. One endeavours to see ordinary birds in ordinary places. Travel will still be necessary and novelty will still be welcome. But it’s just a game.

So to summarise. A Big Year is for lunatics. A Calendar Game year is for under achieving lunatics, those of us who are past peak obsession.

So how is it going? I began the year with a big trip across the top of Oz and then south through outback Queensland and NSW to Victoria. On the 16th of March I was in Melbourne with 274 avian species on the list. 75 days in, 199 species ahead. The return trip to Broome was up through the red centre. Our overdue library books were returned to the Broome Public Library on the 18th of April. 309 species were in the bag, 108 days elapsed. The librarian was thrilled to hear that the buffer was holding steady around the 200 mark.

But of course it gets harder. Broome is a great place for birding. Every Australian birder really must get here. I’d rank it number two after Cairns and the Atherton Tablelands. And it is a place where the odd vagrant turns up. But they don’t rain down. Five months of local birding have added only 20 extra species. 249 days into the year 329 species up. The buffer is shrinking, failure beckons. It must be time for another road trip.

We are well into the dry now. The ground has dried out enough to venture out into low lying parts of Roebuck Plains, to Kidney Bean and Duck Lake. This is home to the Yellow Chat. They are beautiful and not easy to find elsewhere. I added it to the list this morning.

I have so enjoyed this little chat.