Victoria gained independence from New South Wales in 1851. Gold was discovered very soon after. The rush filled Melbourne with new arrivals and as quickly emptied it of able bodied workers. In the 1850’s the place was a disaster, but the money rolled in and by 1860 it was Marvelous Melbourne. The gentlemen of the Philosophical Institute were sure the colony was capable of doing great things.

Off to the west, another colony was on less secure ground. South Australia, far more than the eastern states, is hemmed in by the desert. If, as they suspected, they were confined to a fertile island their prospects for expansion were very limited. Exploration to the north of Adelaide was mainly driven by the hope that new pastures would be discovered. There was also the prospect that Adelaide could become the destination of the newly proposed overland telegraph system that might connect the settled parts of Australia with Asia and the world.

South Australia had an established explorer of the highest reputation, one John McDouall Stuart. Stuart had been with Sturt on his last expedition and then made his name leading small, fast-travelling sorties to the west of Sturt’s track.

The Philosophical gentlemen of Melbourne were honoured with a Royal Charter in 1859 and their Institute became the Royal Society of Victoria. They became even more certain that great things could be done, among them perhaps the first overland crossing of the continent. Committees went to work, money was raised, the Victorian Exploring Expedition came into being, advertisements were placed for a leader and one was appointed.

The expedition was by turns a farce and a tragedy.

On August 20th 1860 26 camels, 23 horses, 19 men and 6 wagons departed Royal Park, Melbourne and managed to cover 11 km. The leader was Robert O’Hara Burke. He had no prior experience of exploration, had no prior experience with camels and could not determine longitude or latitude from astronomical sightings. George Landells was second in command and the camel expert. William John Wills, a young surveyor, was sent along to tell Burke where he was. Tempers were a little frayed in the chaos of departure, some men were dismissed, others appointed right there in Royal Park.

The expedition was the best equipped ever, or so it was claimed. There was, in fact, a mountain of equipment to be transported. At that time the edge of the settled districts was at Menindie (now spelt Menindee) on the Darling River, about 800 km to the north of Melbourne. Cooper’s Creek had been put on the map by Charles Sturt and later visited by Augustus Charles Gregory. That’s another 800 km. Beyond that was unknown territory.

Plan A seems to have been to transport the supplies to form a base camp at Cooper’s Creek. The nature of some of the equipment and the qualifications of some of the personnel implies that Plan A also included a scientific survey of the ground covered, on the other hand Burke was sent on his way with summer coming and exhorted to make all haste, Stuart was in the field and this was to be a race. Plan A was very vague.

The first problem was to shift the mountain of equipment with the means of transport provided. This need not have been a problem at all. Burke had turned down an offer to carry his supplies to Menindie by paddle steamer via the Murray and Darling Rivers for patriotic reasons. This was a Victorian Expedition, it would not be traveling via South Australia!

Instead it traveled very slowly overland, running up considerable over budget expenditure and accompanied by unrest among the troops. It took 56 days to get to Menindie where Landells, second in command and camel expert was fired. In the ensuing argument Burke challenged him to a duel which Landells had the sense to decline. Of the 19 men that left Royal Park 11 had resigned or been dismissed. Eight men had been hired along the way and five of these had also departed. Mr Burke was not a gifted commander.

Burke decided that carrying the mountain of equipment any further was simply beyond the transport at his disposal. Menindie became the base camp. On October 19th 1860 16 camels, 19 horses and 10 men set out for the Cooper. The question regarding race and science was neatly resolved. The scientists and their equipment were left behind. Wills had been promoted to second in command and had to go on because no one else could work out where they were. Also in the forward group was William Wright. Until recently he had managed the nearby Kinchega sheep station. Burke met him in Menindie’s most prominent establishment, Thomas Paine’s Hotel, just days earlier.

Progress was good, recent rain meant there was no shortage of water. They had covered 250 km in 10 days. Burke was impressed with Mr Wright and promoted him to third in command and sent him back to Menindie to bring up further supplies to the Cooper. Thirteen days later Burke established his advanced base camp on the Cooper.

William Wright arrived back in Menindie with a number of problems. He had no written orders, the leader of the party in Menindie would not accept his authority, the local traders would not extend him credit, Burke had for some time been writing rubber cheques. Burke had the best of the horses and camels. There was simply no way to transport tons of goods up to the Cooper. The meat that had come with the expedition had spoiled and would need to be replaced. It would be more than two months before the resupply party would set off.

After about a month at the Cooper Burke divided his party again. On December 16th Burke, Wills, John King and Charley Gray set off with six camels, one horse and 90 days worth of provisions. William Brahe was left in charge of the depot with orders from Burke to remain three months and a suggestion from Wills that he might stay a little longer. Burke expected that Wright would arrive in the interim with further supplies.

After Burke’s death he was hailed a hero. Close scrutiny has led to the verdict that he was more the bumbling buffoon. He was born in Ireland in 1820. He had an imposing physique and an easy going charm. His first career was in the Austrian military and initially successful. It came to an inglorious end when skipping town to evade his gambling debts caused him to be absent without leave. Subsequently he had been a well-liked policeman in the Victorian goldfields. At the time he set off from Royal Park he was pursuing an actress half his age, he left behind a rubber cheque for £96 and a debt at the Melbourne Club of £18 5s 3d. The first 45 days after departing the Cooper were probably the most successful period of his entire life.

Forty five days into 90 days supplies Burke reached Augustus Charles Gregory’s 1856 track across the Gulf of Carpentaria. He had joined the dots. He had supplies to take him home. The coast however was still 200 km away.

He pressed on. This time he was gambling with lives.

The party reached the Flinders River and made camp 119 on its banks. The water was salty and rose and fell just enough to show that they were in the upper reaches of a tidal estuary. The scrub was too dense for the camels to be of use. The next day Burke and Wills pressed on, Gray and King stayed with the camels. The duo were able to get to a point about 20 km from the sea before mangrove swamps became too much even for them and they turned back.

On February 13th 1861 the gulf party left camp 119 and headed south. The Cooper was 1500 km away, 60 days had elapsed of the 90 for which they were provisioned.

At Cooper’s Creek Brahe and three companions were sitting in the shade of a coolibah tree, supplies for them were dwindling, relations with the local aborigines were difficult. The expeditioners had taken possession of a significant resource and had worn out their welcome. The aborigines had taken possession of any item small enough to be carried and they, too, had worn out their welcome. William Wright would have been very welcome but had not turned up.

Wright was at Torowoto between Mutawinjee and the Cooper and making very slow progress. The wet season of the previous year had made reaching the Cooper relatively easy. This year was dry and it was by now mid-summer. A few days later they reached the limit of the available surface water and were trapped for twenty days. Dysentry and malnutrition were becoming a problem.

Charley Gray was the largest of the men with Burke. On equal rations he was the first to die. Prior to his death he had been caught taking food and had been chastised by Burke. Exactly how physically and whether that contributed to his death is unknown. The other three made it back to the depot on Cooper’s Creek after noon on April 21st. The ashes of the campfire were still warm, Brahe and the depot party had left that very morning having stayed there for four months. They had every reason to suppose that the northern party had either perished or having reached the gulf gone east rather than return south. They had buried a cache of food under the coolibah and carved the instruction “Dig” in its trunk. The tree still stands …

At the same time Wright was 150 km further south, his party had left Menindie three months earlier and was in desperate straits. Before long five of his men would be dead from malnutrition. Along the way they had been attacked by a party of aborigines and found it necessary to open fire. One aborigine was presumed killed. Once again the conflict was over access to water equally vital to residents and interlopers. The interlopers were better armed.

Burke, Wills and King dug and replenished their supplies. They had two exhausted camels left. Chasing the depot party seemed beyond them. Burke decided to try to follow Gregory’s route down the Cooper and Strzelecki Creeks to Mount Hopeless and thence to Adelaide. It was indeed a hopeless proposition. They placed their notes in the trunk that Brahe had left for them and reburied it. They made no marks on the coolibah that would inform of their presence and set off south west.

Brahe going south met Wright coming north. The pair returned to the Cooper. Found no evidence of Burke’s return, saw no reason to dig, and headed south again.

The trio on the Cooper eventually realised that they were not going to walk out. Assistance from the local aborigines was their only hope and to some extent it was forthcoming.

Wills returned alone to the dig tree and deposited his diary there. He was unaware that Wright and Brahe had been there whilst he was further west. He returned to his companions only to find that Burke had spoiled relations with the aborigines by firing his revolver over the head of a young man who had helped himself to a piece of oil cloth. He repeated the trick soon after when the locals offered him some fish and nets. The aborigines then kept away. Burke had also had an accident whilst cooking. The subsequent fire had destroyed most of their remaining possessions.

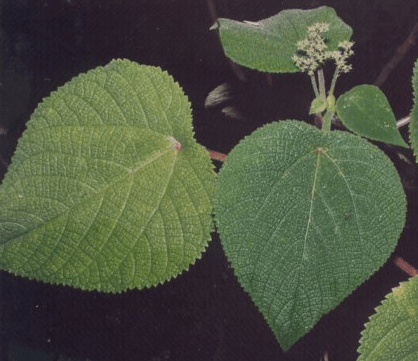

The trio was left to subsist on nardoo, a plant that was readily available but which needed to be prepared properly prior to eating. They had been introduced to nardoo by the aborigines but were ignorant of the correct process for its preparation. It was Wills that weakened and died first, then Burke. King had done nothing to make himself unpopular with the aborigines and one man was not so great a burden. He was taken care of by the local people.

Back in Melbourne people began to wonder where the expedition had got to, no one more vocally than Dr W J Wills father of William Wills. The august gentlemen of the Royal Society were eventually stirred into action and in June formed committees to see what could be done. The result was no fewer than five relief expeditions setting out from all quarters of the compass. King was rescued. The bodies of Burke and Wills were brought back to Melbourne and were the stars of Victoria’s first state funeral. More than 11,000 km of difficult terrain were covered by the relief expeditions and not one further life was lost. This exploring business was not so dangerous if you knew what you were doing.

In 1862 John McDouall Stuart became the second person to lead a party from the south coast to the north. He made it back again. The overland telegraph was built along the route he established, Adelaide, Alice Springs, Darwin. The latter remains the only substantial town on Australia’s north coast. If Google maps is consulted on the route to take from Melbourne to Darwin it will take you to Adelaide and then follow Mr Stuart’s route north. The gentlemen of the Royal Society would be horrified.